Why the Stages of Grief are Unhelpful to Those Who are Grieving

What Are the 5 Stages of Grief?

Developed by Dr. Elisabeth Kübler-Ross in the 1960s after studying terminal cancer patients facing their own mortality (i.e., how the dying come to terms with their own approaching death), they were incorrectly applied and popularized to the bereaved (i.e., those who grieve for a loved one who has died).

Unfortunately, this model can bring unnecessary suffering to grievers, when they worry they aren’t conforming or “doing it right” according to these stages. Even Dr. Elisabeth Kübler-Ross publicly stated this is not meant for the bereaved, but due to it’s simplicity, it was commercialized and spread as fact.

Why might the theory of stages be unhelpful (or even harmful) to those who are grieving?

Misleading/Unrealistic Expectations

Stages provide no variation for why someone may experience varying degrees and kinds of distress at different times.

Stage theory also leads to many people feeling impatient because they think they should be feeling better “by now.”

Research has shown that grief is complex and personal and doesn’t fit into neatly categorized stages. Factors such as age, gender, ethnicity, culture, and religion all shape the way we grieve. Other factors, such as our relationship with the person who died or the way they died, also influence our grief response.

Inadequate Support

Stage theory does not help us identify those at high risk or with complications in their grieving process, such as complicated relationships with the deceased or traumatic and out-of-order deaths (like the death of a child).

Stages do not account for secondary stressors or the “ripple effects” of grief, which can have large implications to a griever’s ongoing life changes, roles, identities, etc.

Grief varies just as greatly as our personalities and preferences - Support for the bereaved should have the freedom to be as unique as the person experiencing it (and the situation/death that has occurred).

Lack of Awareness of Other Grief Effects

Stage theory denotes some affective states, others cognitive processes; there is a mixture of different types of constructs which do not fit coherently or sequentially together.

Stage theories also imply that over time, our grief gets smaller, which allows us to get over or move on from our grief. However, this is not usually the case and the idea that someone needs to forget their loved one is one of the most problematic messages.

Grief is an all-encompassing experience that is likely to impact someone’s emotions, thought processes, physical sensations, spirituality, and even behaviors. Someone’s daily life may be impacted very little, or hugely, depending on the death and surrounding circumstances. Awareness of all the ways one can be impacted in grief is vital to healthy integration of the loss in one’s life.

Of Note: Dr. Elisabeth Kübler-Ross’s “Five Stages of Grief” is not the only grief “stage” or “task” oriented theory - any of them can have the same potential detriments to those experiencing grief and should be considered carefully.

Grieving is far more complicated and nuanced than 5 stages.

Of course it would be great if there was such a simple process we could follow to work through the discomfort and pain of grief.

It would be reassuring to know that while we’re feeling really depressed right now, once we get through this stage, we’ll be okay with ourselves and life again.

But we humans, our relationships with one another, and our experience of mortality are much more complex than a 5-stage process.

Grieving is a natural response to a death loss - there are no short-cuts or a way to bypass it.

So - are there theories to help us understand and navigate grief?

Below are a couple of the theories I have experienced (professionally and personally) as the most supportive to those navigating grief.

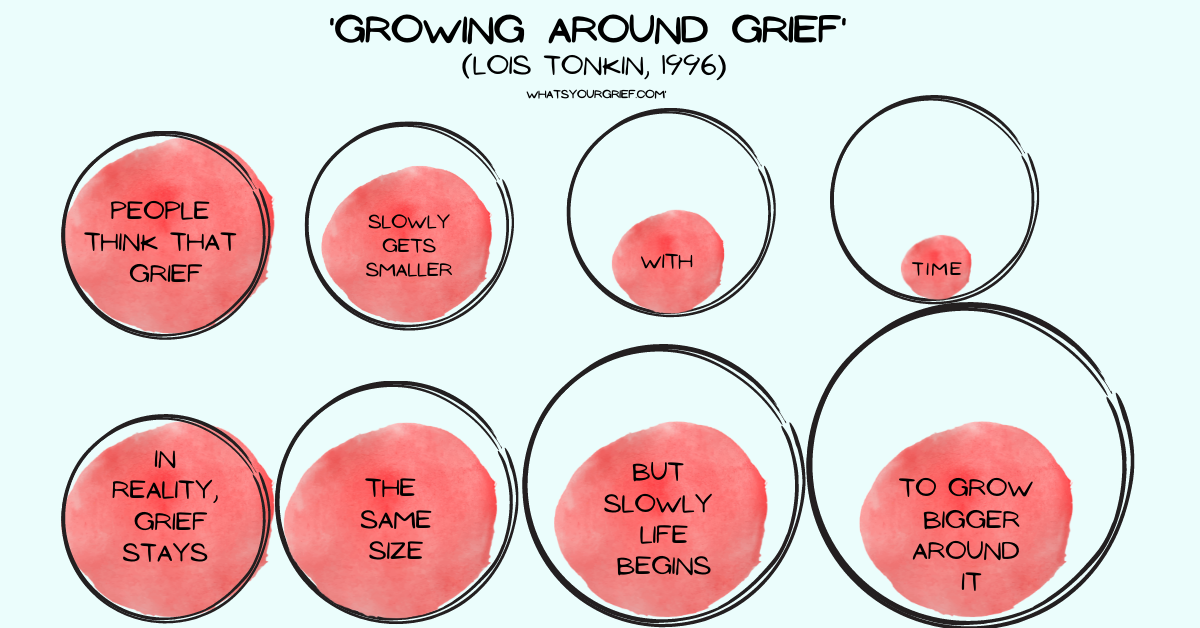

The idea that time heals all wounds was challenged by Dr. Lois Tonkin in 1996 when she developed the ‘growing around grief’ model. This model acknowledges that grief isn’t necessarily something we heal from or something that shrinks over time. Instead, it suggests our grief stays the same, but we grow our life around it, so our grief no longer consumes us as it did in the early days of our loss.

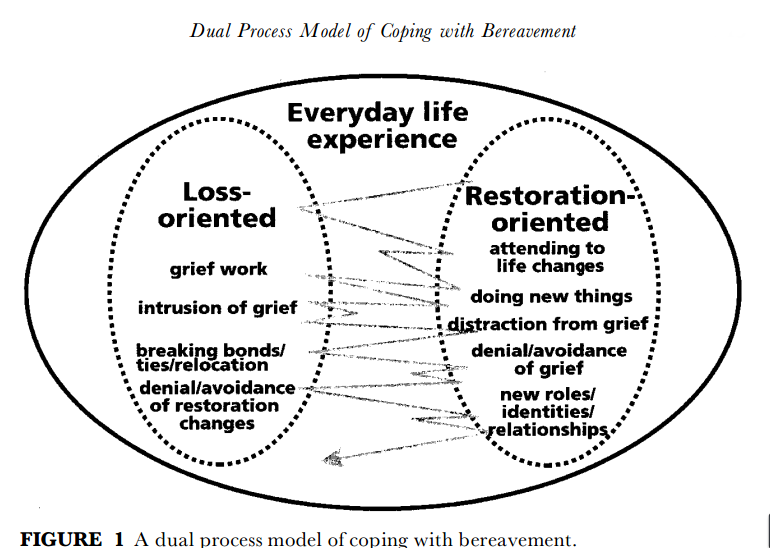

Oscillation is the crucial component of the Dual Process Model (DPM), developed by Margaret Stroebe and Henk Schut in 1995. They suggest that healthy grieving means engaging in a dynamic process of oscillating between the stressors of loss-orientation (i.e., focusing on and processing the loss of the person who has died, along with our relationship with that person) and the stressors of restoration-oriention (i.e., secondary losses and stressors, such as fulfilling roles the person who died used to do and/or rebuilding of everyday life). Both require coping.

Other definitions of “grief work” may indicate a griever must face the pain of the loss head-on, which is emotionally and physically exhausting, but is thought to be “crucial to healthy grieving.” However, the DPM argues that to “avoid, deny, or suppress” certain aspects of grief is not only normal, but a healthy and important part of grieving.

In summary, and if there is a main takeaway from the DPM, it’s that it's okay to experience grief in doses. At times you will face your loss head-on, at other times you'll focus on practical needs and life tasks, and once in a while you will need to take a break or find respite.